Our Cathedral in San Jose invites a lay person each year to lead a reflection at the noon hour on Good Friday as a prelude to the Liturgy of the Veneration of the Cross led by the Bishop later in the afternoon. This year, I was invited to do this.

We adapted the Office of Readings for Good Friday for this assembly quite unfamiliar with the structure and included a gradual extinguishing of candles throughout the prayer, a gesture that comes from the liturgy of Tenebrae. The sacred reading assigned for the Office came from the Catecheses of Saint John Chrysostom, a beautiful short reflection on the power of the blood of Christ (see the Office of Readings link above for the text).

Our Cathedral Basilica of Saint Joseph has beautiful trompe l’oeil art throughout the walls and ceiling with wonderful symbolic images that catechize as much as they delight. Over the altar, which sits in the middle of the church, is a dome, and around the dome are four medallions over the four aisles leading to the altar. Over the center aisle at the edge of the dome is a medallion with the image of a pelican (here’s a great photo of the entire dome except for the pelican). Below is the reflection I shared on this image and its connection to the blood of Christ.

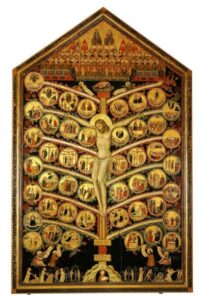

In the center of the painting, dominating the entire panel, is a life-sized image of Christ crucified, not on a cross but on a tree. The painting is called “Tree of Life.”

The tree has 12 branches, six on each side. Hanging from each branch are three or four round medallions, almost like Christmas ornaments, and in each medallion is a smaller picture showing some event in Jesus’ life, from the angel Gabriel’s announcement of his conception, all the way to his burial, resurrection, and ascension.

Just under the lowest branches are images of the prophets from the Old Testament holding unfurled scrolls, as if they were decorating the tree with these garlands.

And beneath them, at the very bottom of the panel, at the tree’s roots, stand Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, tiny figures under this massive tree. To the left of them, we see God creating them; to the right, we see God expelling them from Eden.

At the very top of the panel are the saints and angels in heaven, with Christ and his Mother seated on thrones above them all.

And straight down from there, about two feet, sitting on top of the tree just above Jesus’ head, is a bird—not a partridge, but this…a pelican.

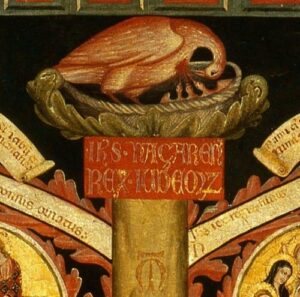

And straight down from there, about two feet, sitting on top of the tree just above Jesus’ head, is a bird—not a partridge, but this…a pelican.

The myth of the pelican goes like this.

The great mother pelican protected her young with all her might. But nothing could protect them from the great famine that came across the land. As she watched her chicks dying beneath her wings, she did the only thing she could. She pierced her own breast with her long sharp beak, and blood flowed down upon her flock. Their weak necks strained upward to catch the drops. And as the mother’s blood flowed from her side, her children became stronger and came back to life as she, herself, gave up hers.

The myth of the pelican goes back all the way to the earliest days of Christianity, back to Egypt where the Israelites first sprinkled the blood of a lamb on their doorposts, so that the Angel of Death may pass over them, and thus their own first-born children were spared.

If you take a look at our own pelican here, you can see her drops of blood that flow from her side.

Saint Thomas Aquinas called Jesus, Pie pellicane, sweet, loving, merciful pelican.

All his life, out of love for his own, Jesus gave himself away…until he had nothing left to give except his very blood.

Jesus suffered and paid a great price, not because our lives could be bought and sold like merchandise, his for ours. No, Jesus simply loved us so much that he gave everything he had to see us live again. For the result of love, the outcome of love, the fruit of love, the cost of such great love, is always sacrifice.

No one can say for certain, then, that there is a “reason” for suffering or some kind of “meaning” to it, as if God makes us suffer on purpose to “teach us a lesson” or to make us better persons.

Yesterday, a good friend of mine died of cancer, while another friend gave birth to her daughter. Yesterday, my grandmother celebrated her 98th birthday, while my childhood friend sat in a hospital room with her young son wondering if he would live through the night. Yesterday, a church in Oakland mourned seven people who lost their lives by a desperate and deranged act of a gunman, even as at the same time they prayed for mercy and forgiveness for the man who confessed to this horrific crime.

No one can say there is reason or logic to our suffering. But we who stand here at this Tree of Life can say there is a reason to hope even in our suffering—Jesus, who accompanies us, all of us, the innocent and the guilty, in our suffering and in our joys; Jesus, whose blood brings us all back to life.

But there is a darker version of the myth of the pelican. It goes like this.

Although the mother pelican cares so much for her young, her children strike at her with their own beaks. And out of anger and fear, she kills them all. But after three days of grieving over what she had done, she pierces her own flesh and the blood from her side drips upon her children and brings them back to life.

Sometimes, we can be like that mother pelican, doing the best we can for those we love, giving all we have to our families, our work, our churches and governments, our friends. And still, in the end, we are betrayed. Our families fall apart, jobs are lost, leaders become corrupt, and friends leave.

Out of anger, fear, hurt, confusion, we strike back and shield ourselves from further pain. And we slowly stop giving ourselves away for fear of losing it all. And as we build that shield around us, making it thicker with suspicion, cynicism, slander, hatred, and all kinds of ways that keep us from being vulnerable to another, slowly, the light that was once in us, begins to fade and grow dim, until it suffocates within the walls we have created between us, our God, and the person God created us to be.

That is why we come back, Sunday after Sunday, here to this altar, that sits under the sign of the pelican and in the shadow of the Cross, to be fed once again with the life-giving blood of Christ. To be drenched once again by the flood of grace that flows from the side of Jesus on the Tree of Life, that the walls we have built around our hearts may be softened, that Christ may pierce the hard, resistant skin we have wrapped around our souls (Richard Rohr), so that we too may again love one another as he has loved us.

Come, let us glory in the Cross of Christ, from whom we receive mercy, light, and life in time of need.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful reflection. It is especially rich in the manner in which it directs us back to the vast corpus of visual art that, when properly explained, deepens our understanding of key doctrines and liturgical traditions.

thank you for this inspired/inspiring sharing of the significance of the pelican. i had heard cursory descriptions and parts of legend but never had it divulged completely–so richly.

We have the pelican on the front of our altar. Beautiful symbol and exciting to proclaim the relevance!