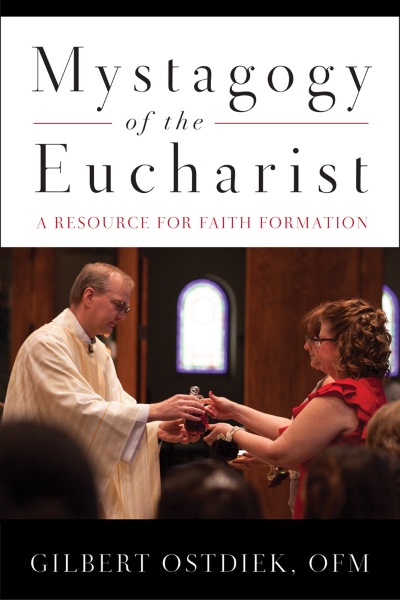

I recently read a book about mystagogy that can be helpful for RCIA teams. In Mystagogy of the Eucharist, Gilbert Ostdiek, OFM, makes the point that we have to think of mystagogy as more than just the final period of the initiation process. It is part of the broader ministry of catechesis. His book and the method of ministry he describes are intended for “those who are responsible for the formation of worshippers” (xii). Since every Christian and catechumen is worshipper, that is a pretty big audience. It includes pastors, liturgists, choir directors, youth leaders, school teachers, and catechists of all types. And it includes RCIA teams.

However, as the title indicates, this is a method for mystagogy of the Eucharist, which the catechumens will not participate in until after their baptism. Even so, Ostdiek’s insights about the mystagogical method can help us in our formation of catechumens throughout their process.

God is revealed through symbolic action

Ostdiek focuses the symbols of the liturgy, many of which the catechumens encounter when they participate in the Sunday liturgy of the word and other ritual celebrations in the parish. Also, while the liturgy is the premier place in which God is revealed to us, the catechumens encounter the Holy in many signs and wonders outside the liturgy as well. Ostdiek’s method could easily be applied to any symbolic experience, liturgical or otherwise.

Symbols of the Holy, especially liturgical ones, are not simply inert objects that weakly represent some bigger, better reality. Liturgical symbols are “cosmic elements, human rituals, and gestures of remembrance of God [that] become bearers of the saving and sanctifying action of Christ” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1189).

Sometimes as catechists, we are tempted to discount the power of the liturgy to teach.

The privileged place for catechizing

Sometimes as catechists, we are tempted to discount the power of the liturgy to teach the catechumens what it means to live as a Christian. The Catechism reminds us, however, that the liturgy is “the privileged place for catechizing the People of God” (1074).

That doesn’t mean that we have a commentator explaining each piece of the liturgy as it happens. Nor does it mean we keep the assembly hostage for three or four minutes after communion while the presider “catechizes” his captive audience. It certainly doesn’t mean we should start doing “teaching Masses.”

The way liturgy catechizes, says Ostdiek, is first of all by first of all making sure that “those who plan and lead the celebration ‘are thoroughly imbued with the spirit and power of the liturgy’ (Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, 14)” (8). Next, the celebration must correspond “‘as aptly as possible to the needs, the preparation, and the culture of the participants’ (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 352)” (8). Finally, the symbols of the liturgy must be “shaped with loving care and bear the stamp of their maker’s hand…and yet ‘are able to bear the weight of mystery, awe, reverence, wonder’ (Built of Living Stones, 146-148″ (8).

None of these three prerequisites are usually under the control of the catechist. However, Ostdiek says this is only the beginning of mystagogy. Good liturgy, when celebrated according to the criteria above, communicates God’s self. Liturgy has meaning. The next step in mystagogy is for the catechist to ask two questions about the liturgical experience: “What happened?” and “What did it mean?”

Listen to what the participants already know

Notice that the catechist first asks and listens. Mystagogy is not primarily an explanation of the liturgy. It is a guided reflection upon the encounter the seeker has had with the Divine Mystery. Ostdiek says, “I have learned to trust the participants already know more than I had expected…. One of the great benefits of mystagogy is that it enables participants to name their own experience and to learn from it” (17).

My only caution about using Ostdiek’s book as a guide for your RCIA formation would be the same one he offers. The sample sessions he provides “are not meant to be actual presentations. They simply provide background information and ideas for the facilitator” (21). Slavishly following Ostdiek’s examples without making them your own, using your own insights and resources, will lead to flat, uninteresting presentations that might do more harm than good.

My suggestion would be to read Part 1 of Mystagogy of the Eucharist (about 20 pages) slowly and carefully, with highlighter in hand, grounding yourself in the principles of mystagogical reflection. Then read the rest of the book more casually as a source of inspiration for your own creative mystagogical processes with your catechumens.