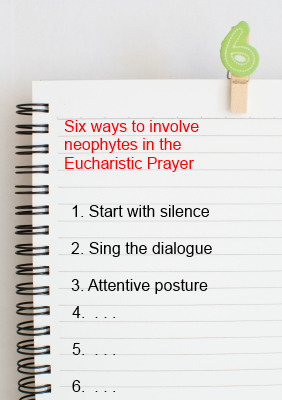

For the neophytes, the Sundays of the Easter Season are the primary setting for mystagogy. One reason that is so is because it is during this time when the neophytes will first pray the Eucharistic Prayer with the rest of the baptized faithful.

For the neophytes, the Sundays of the Easter Season are the primary setting for mystagogy. One reason that is so is because it is during this time when the neophytes will first pray the Eucharistic Prayer with the rest of the baptized faithful.

The Eucharistic Prayer is supposed to be a climactic moment in the liturgy. If there is ever a time in the Mass when we are supposed to be fully conscious and active, this is it. Yet, it can be difficult to make this part of the liturgy as active as it needs to be.

The suggestions below will require the cooperation of the presider, the musicians, the liturgy planners, and the members of the assembly. As RCIA teams, you may not have equal amounts of influence with all those groups. But you can use the influence you do have to begin to improve the participation levels.

To the extent you can increase the participation of the assembly, you will have given the neophytes a better experience of the period of mystagogy.

Start the prayer in silence

Just before the dialogue that begins the Eucharistic Prayer (“The Lord be with you. And with your spirit. Lift up your hearts…”), we have the preparation of gifts (“Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation…”). Oftentimes, these two elements of the liturgy run together and seem to be one long block of text. Add to the participation in the Eucharistic Prayer by adding a profound silence between the two.

Sing the dialogue

Presiders can also enhance participation by singing the dialogue. Anyone can sing a simple chant tone. The truly musically challenged can sing the entire dialogue on a single note. However, an investment in a one-hour voice lesson with the parish or diocesan musician will increase confidence and give the presider the ability to sing a still-simple but slightly more interesting chant.

Pay attention to posture

There are different postures during the Eucharistic Prayer. However, slouching and half-sitting are not among them. Teach the neophytes to always be attentive to their posture. Whether standing or kneeling, think of “leaning into” the prayer.

Acclaim well

You will need the musicians’ help with this one. That acclamations (Holy, holy, memorial, amen) must be singable by non-musicians. People who are naturally gifted signers forget this sometimes. You can help remind them by praising the musicians when they choose acclamations that your neophytes actually sing.

Integrate the supper narrative into the rest of the prayer

The supper narrative is the part when the priest says: “Take this, all of you, and eat of it…” and “Take this, all of you, and drink from it….” When I was a kid, we called this “the consecration,” and it still goes by that title today (“institution narrative and Consecration,” GIRM 79).

However, in the olden days, we thought of the consecration as The Consecration — as though the rest of the prayer wasn’t all that important. For some of us, there is a bit of that thinking that sometimes creeps back into the way the Eucharistic Prayer is prayed today. The elevation of the bread and wine is exaggerated and extended; the genuflection might also be exaggerated and extended; bells are sometimes rung (which is allowed, but I think doesn’t really help the flow of the prayer). The United States Bishops said that the supper narrative is part of a larger whole, and it ought to seem that way:

This narrative is an integral part of the one continuous prayer of thanksgiving and blessing. It should be proclaimed in a manner which does not separate it from its context of praise and thanksgiving. (Introduction to the Order of Mass: A Pastoral Resource of the Bishops’ Committee on the Liturgy, 90)

Make the doxology doxological

The doxology is the part that begins, “Through him, and with him, and in him….” “Doxa” means “praise.” The conclusion of the Eucharistic Prayer should have the character of exuberant praise. The presider should definitely sing the “Through him…” part, and the assembly should respond with a vigorously sung Amen!

As I said, RCIA teams will not have equal influence over all of these aspects of the praying of the Eucharistic Prayer. But if you can take one small step towards more participative prayer, you will have begun to get the neophytes more involved. After a while, try another step. And then another.

![]() Check out this webinar recording: “How to Teach the Eucharistic Prayer.” Click here for more information.

Check out this webinar recording: “How to Teach the Eucharistic Prayer.” Click here for more information.

What has worked for you?

What have you done in your parish to help the neophytes participate fully in the Eucharistic Prayer? Please share your thoughts in the comment box.

Now that I’m a little bit older, I’ve observed the following: For children, they are little sponges; less conceptual, more cognitive. They learn facts and retain them very well. When the eucharistic prayer is broken down into all of its components and each explained, they can put it all together. They even say, “what about the rest of it?” Of course they just went through the rest of it, but the point being that it isn’t just one long boring prayer.

For older adults, I see a lot of trouble with ‘big’ church words, like consecration, consubstantial, incarnate, etc. They will often recount their earlier childhood or young adult experiences and ask why things changed. And they ask why we used to kneel but now the pastor say we have to stand in unity.

Again, breaking it all down to the individual parts helps with those ‘Oh’ moments tremendously.

Young adults. Ah yes, a group that eagerly captures the existential mood and meaning of the prayer for their own. This is great! New words and phrases make it easier for them to right the wrongs of this not so perfect religion that was passed on to them, but it makes them a little bit exclusive. It reminds me of when I was a teenager and new it all. My dad would just say, “you haven’t lived yet”.

These are just some of my reflections I thought might be worth sharing. I always like your presented information that helps me reflect on my experiences. Thank you.

A priest presider I know well who leads the Euchariastic Prayer very prayerfully slows down as

he comes to the prayer asking the Spirit to overshadow the gifts of bread and wine (and ourselves)

and lays his hands carefully over the gifts; it’s the power and grace of the Holy Spirit that consecrates

the gifts, transforming them into the body and blood of Christ. (not the narration of the Supper:

“This is my Body…my Blood”) and the Elevation.

Nick: As part of our RCIA mystagogical sessions, we took some time reflecting on the exsultet as a springboard – including some discussion on stories from salvation history (heard in our Easter Vigil readings, sung in our psalms, and ritualized during the service of light) – but also some reflection on the eucharistic prayer, since the Exsultet follows a eucharistic prayer pattern.

@Steven: thanks for your comment! And thanks for highlighting your reflections with young adults. My experience with college students is that they still see the EP as a long prayer with moments for the assembly to “chime in” as if the EP is not for them and they just listen passively rather than respond with enthusiasm to the musical acclamations. I like your comment of capturing the meaning of the prayer in their own. I will ask some of my students what they think of the EP that day.

Now, it also gets me thinking about EP for Masses with Children – with all the insertion of acclamations. Do communities use it with success of a more conscious participation? I have actually never experienced this EP as a child – maybe I would have benefitted from it? Then again, I was a child with the previous translation of the Missal.

@judy: I like that image. It reminds me of the importance that priests have in liturgical presiding and how they must act with grace so that they themselves can “speak” of themselves as a symbol for the assembly. How has this example of the priest affected your life? Where have you seen God in that?

@justn – oooo I forget about that juxtaposition of the EP with the Exsultet – do you have any resources of a comparison between the two? Article? Book? Dissertation?